Secure Multiparty Computation (MPC)

This post is a short introduction to “Secure Multiparty Computation (MPC)”. The content is loosely based on an article of the same name by Yehuda Lindell [Lindell20] (link).

Motivational Example: 2-party auction

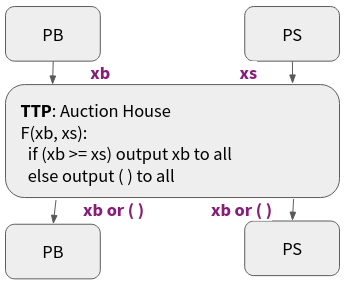

As with explaining most things, it is usually good practice to start of with an example. Let us consider an auction. The auction has two main parties, the buyer $PB$ and the seller $PS$. The buyer wants to buy an item, and is willing to pay up to his bid price on the item $xb$. The seller wants to sell an item, and is willing to sell the item for up to an asking price $xs$. The auction usually involves a trusted third party (TTP). Each party gives their respective inputs (bid/ask) to the TTP, if the bid $xb$ is larger or equal to the ask price $xs$, then the TTP will declare the item as sold for the bid price $xb$, this information is then passed back to both parties. If the bid price $xb$ is smaller than the ask price, the auction will declare the item as not sold, and pass this information back to the parties.

Figure 1: TTP Auction

In the way we described this, the TTP can be modeled as a trusted (or as we also call it, ideal) functionality, that computes a function with inputs from the parties and outputs to the parties. What about the security of using a TTP? By definition, the TTP can be trusted to a fault, it is incorruptible. This, however, is somewhat idealistic. In the real world there may not be any TTP, there is plenty of evidence of corruption in cases when a TTP would act in malicious ways. But, is there a better way of doing these things? Perhaps. Secure multiparty computation (MPC) is a technique for replacing a TTP with a secure protocol that involves the same parties, but does not involve a TTP. We will delve deeper into this later on, but we will call this that the MPC protocol securely realizes, or emulates, or implements, the TTP ideal functionality.

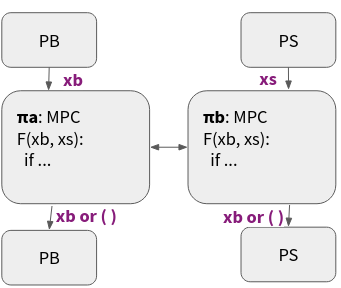

Figure 2: MPC Auction

What are some important properties of a MPC protocol that implements this auction functionality. A few come to mind:

- Privacy: neither party should learn about the other parties bid/offer (unless it can be deduced from the final output).

- Correctness: the auction output is correct.

- Independence of inputs: $PB$ should not be able to chose its inputs to the auction based on $PS$’s inputs, for example $PB$ could choose $xb = xs$, we don’t want this to be possible.

- Guaranteed output delivery: if both parties have put in a bid/offer, then both parties should receive an output.

The active reader might recognice that the TTP auction has these properties. The TTP is correct, does not leak privacy-information, and so on. This intuition is correct, and as we will see later on, instead of defining the security of an MPC protocol by a list of properties, we instead define it by ideal TTP functionality that it tries to securely realize or implement. That is, in order to reason about what properties the protocol has, it suffices to reason about the properties of the ideal TTP functionality that it implements.

With this introduction we have hopefully staged it well for continuing with general MPC.

What is MPC?

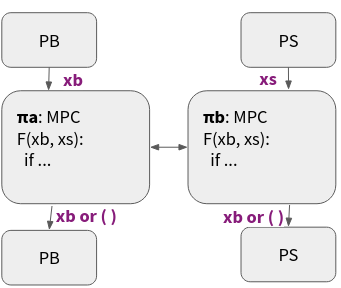

MPC is the secure computation involving multiple parties of a function F. The notation that we will use is the following:

- Parties: $P1, …, Pn$

- Inputs: $x1, …, xn$

- Outputs: $y1, …, yn$

- Function: $y1, …, yn \leftarrow F(x1, …, xn)$

- Protocol instances: $\pi 1, …, \pi n$

Each party $Pi$ passes its input $xi$ to the protocol instance $\pi i$, the protocol then may interact with other protocol, and computes the output $yi$ which is passed to the party.

Figure 3: MPC

But what does it mean to perform the “secure” computation of a function? As we discussed earlier, this could mean that the protocol has the properties:

- Privacy:

- No party should learn about the other parties’ inputs (unless it can be deduced from the final output).

- Correctness:

- The function is computed correctly.

- Independence of inputs:

- No party should be able to choose its inputs based on other parties’ inputs.

- Guaranteed output delivery:

- No party should be able to prevent other parties from receiving the output.

- …

Or, we can also think of it as the MPC protocol “securely realizes”, or implements, or emulates, the TTP execution the function.

But what are we secure against? We want our protocol to be secure against adversarial parties that participate in the protocol. There are two classes of adversaries that we typically consider:

- Semi-honest adversary:

- The semi-honest adversary follows the protocol.

- However, the adversary may attempt to learn information from the protocol execution that the adversary was not supposed to learn. Example, this might be that the adversary tries to learn about other parties inputs from the exchanged messages, this would break the privacy property as we defined above.

- Malicious (Byzantine) adversary

- The malicious adversary may deviate from the protocol arbitrarily.

- In particular, it may attempt to learn information, corrupt the protocol, and collaborate with other adversaries.

Both types of adversaries have important applications. Many problems may be simpler to solve, and the solutions more efficient, for semi-honest adversaries. Whereas malicious adversaries is more suitable for applications that run between parties that don’t trust each other.

In general, MPC can be achieved for any general functionality, for any threshold of adversaries. Although, in practice, because of the computational overhead from secure computation, this is not the case for all functions. There are some important distinctions for the feasibility, for example, for the case of when the number of adversaries is more than half of the participating parties, then for a general MPC function we cannot guarantee output delivery of fairness. You can find out more about this in the introductory MPC article by Lindell [Lindell20].

How to Define the Security of MPC?

In the introductory example we attempted to define the security of the auction through two approaches.

The first approach is to list the properties that the protocol should have, and prove that the protocol indeed has these properties. Although this might seem like a good idea, there are some issues with this approach. The main issue is that we might have missed an important property, and forgotten to add it to the list. Ideally, we would like to have an approach that covers all possible attacks, instead of an approach that defines which attacks (properties) it covers.

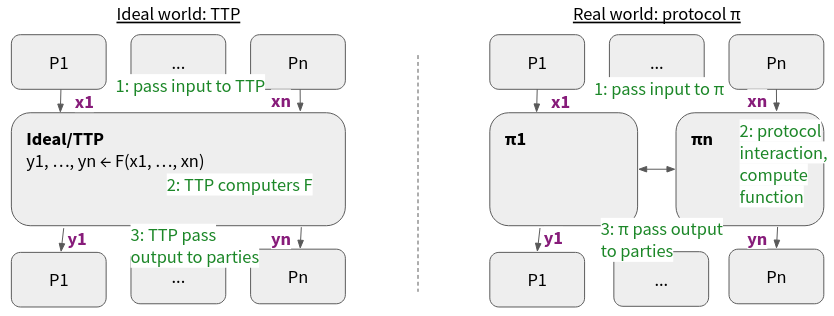

The second approach would be what is known as the real/ideal paradigm.

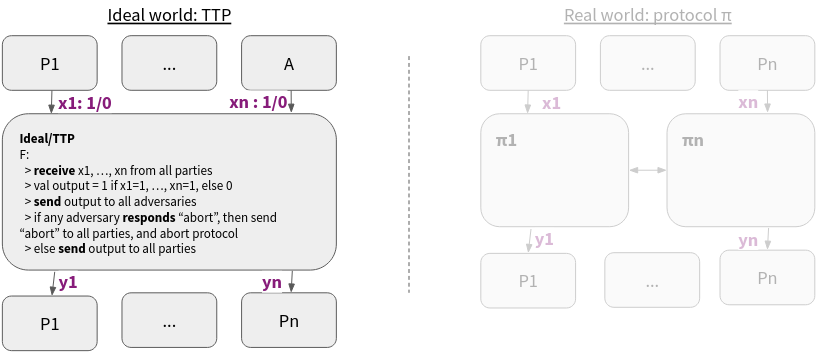

Figure 4: Real/Ideal Paradigm

In the ideal world, there exists a trusted third party (TTP), also referred to as the “ideal functionality” F, that computes the function for the parties. In the real world, no such TTP exists, but the parties instead invoke a protocol $\pi$ that computes this function.

How do we reason about the security and correctness of our protocol in this paradigm? First, we define the ideal/TTP functionality F, what it computes and how it interacts with each party. Then, we prove that the protocol $\pi$ securely realizes the ideal functionality. This involves a proof technique which is called simulation (for more information check out [Lindell17]). Using simulation we can show that the protocol is as secure/correct as the TTP, by showing that if we can break the protocol through some attack, then we can also break the TTP or break one of the assumptions.

A consequence of this is that the party can interact with the protocol as if it was interacting with the ideal/TTP functionality, and it suffices for the party to understand the ideal functionality to use the functionality.

The definition of security in the real/ideal paradigm can be used for any general computational task, and it covers all attacks. But, there is a twist, what if we don’t want to, or, don’t need to be secure against certain attacks. For example, as mentioned above, it is not feasible to have “guaranteed output delivery” for the case when $t \geq n/2$ more than half of the parties are malicious. How can we then relax our definition to also define functions in this case? This is a subtle detail, we can define these attacks in the definition of the TTP functionality. In the example of an and-gate that computes the logical and of all parties’ inputs, we have added the possibility for the adversarial party to abort the protocol (as well as breaking the fairness).

Figure 5: Example of an ideal function definition with an attack

The functionality sends the output to the adversary, and waits for the response from the adversary to either abort or continue the protocol.

Use Cases of MPC

There is an easy way of finding use cases for MPC. First, identify a problem that relies heavily on a TTP. Then, replace this TTP with a MPC instance. There are many general purpose MPC compilers that can be used for compiling a general function to a secure MPC protocol: SCALE-MAMBA, MP-SPDZ, Obliv-C, etc. But, there are more concrete examples of use cases.

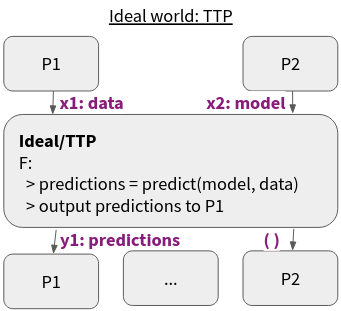

Privacy preserving computation is an often quoted use case. In the example graphic that is shown here, two parties, the data-owner and the model-owner, are using an ideal functionality to apply the model to the data to generate predictions. In particular, the data owner should learn nothing about the model (except what may be learnt from the output), and the model owner should learn nothing about the data. This, and various derivations of it, might be useful for when the data is critical and may not be shared with other parties.

Figure 5: Ideal functionality for privacy preserving computation

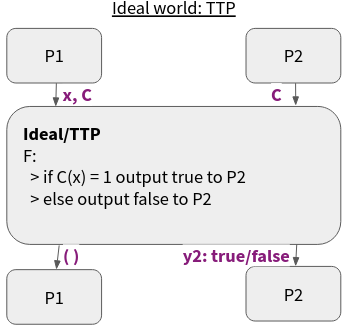

Another application of MPC is for Zero-Knowledge Proofs (ZKP). Although, ZKP can be classified as its own field, MPC is a general concept that contains ZKP. The structure of a ZKP is shown in the figure below. Party P1 wants to prove to P2 that P1 “has knowledge of” some $x$ such that $C(x) = 1$ for some circuit $C$, without revealing any information about $x$ to P2 (besides that $C(x) = 1$). Note, in practice this would be circuit that is hard to invert, such that it is difficult to find such an $x$ that evaluates to $C(x) = 1$ without additional information. This is a somewhat strange concept, but it can be achieved with MPC.

Figure 5: Ideal functionality for zero-knowledge proof of knowledge

The last use case is for threshold signatures and threshold cryptography. The main idea behind threshold cryptography is to split data into smaller pieces (secrets), such that a threshold at least $t$ of pieces is needed to recreate the data. This has some important implications, we could for example split user data across $t+1$ data centers, such that a hacker would need to hack at least $t+1$ data-centers to recover any useful information.

Final Notes

MPC is feasible, but it can be very slow. For example, computing the inner product of two 100’000 element vectors was benchmarked to take 0.02 to 700 seconds depending on the protocol [Keller20], this is more than 1’000 times slower than for an optimized non-secure implementation.

As a final note, it is good to keep in mind is that there are no restrictions on the input and output to/from a protocol. The adversary is allowed to input anything to the protocol. Similarly, the adversary is allowed to learn anything it can learn from the output. There are other techniques for dealing with these issues.

If you want to learn more, I recommend the article which this post is also based on [Lindell20], but also the book “A Pragmatic introduction to Secure Multi-Party Computation” [ERK17]. For information on how to prove the security of MPC I recommend [Lindell17]. If you want to play with general MPC frameworks [Keller20] is a good starting point (as is SCALE-MAMBA).

References

- [Lindell2020] Lindell, Yehuda. “Secure Multiparty Computation (MPC).” IACR Cryptol. ePrint Arch. 2020 (2020): 300.

- [Keller2020] Keller, Marcel. “MP-SPDZ: A versatile framework for multi-party computation.” In Proceedings of the 2020 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, pp. 1575-1590. 2020.

- [Lindell2017] Lindell, Yehuda. “How to simulate it–a tutorial on the simulation proof technique.” Tutorials on the Foundations of Cryptography (2017): 277-346.

- [EKR17] Evans, David, Vladimir Kolesnikov, and Mike Rosulek. “A pragmatic introduction to secure multi-party computation.” Foundations and Trends® in Privacy and Security 2, no. 2-3 (2017).