MPC Study Group: Oblivious Transfer Extension

In this week’s Zoom Meetup we discussed oblivious transfer and the oblivious transfer extension [1, 2]. You can watch the virtual meetup (it was a great presentation):

These are my personal study notes, so please refer to the references to verify any information in this post. The content of this post is mostly based on [1].

Introduction

Oblivious transfer (OT) is a fundamental building block in MPC. As we have discovered in previous weeks, it is used in Yao’s garbled circuits, beaver triples, and gmw. Besides its use for practical algorithms and implementations, there is a theorem that states that oblivious transfer is complete for secure multi-party computation tasks: assuming that you have an instance of oblivious transfer, then there is a secure MPC protocol for any $f<N$ and any functionality $F$.

There are many reasons to study oblivious transfer, and this week we studied the 1-2 oblivious transfer extension in the semi-honest security model. The OT extension is more performant than the base OT. The base OT protocol that we present requires three public-key operations per OT. Because public-key operations are expensive we would like to reduce the number of pk-operations in our protocol. For example, in the GMW protocol we need $O(a * n^2)$ number of OTs where $a$ is the number of and-gates in the circuit, oblivious transfer is the main bottleneck of the protocol. The OT extension, in contrast, uses $k$ instances of base OT, and generates $m$ instances of OT that don’t require public-key operations, with $m \gg k$ being much greater than $k$. Thus, we can greatly improve the performance of OT and of protocols that use OT.

Definition

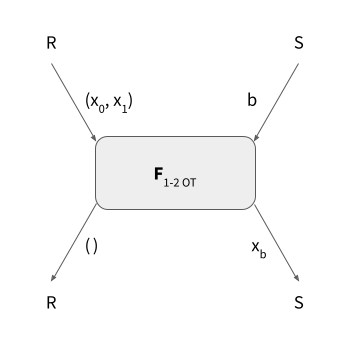

In 1-2 oblivious transfer there are two parties: the sender $S$ and the receiver $R$. The sender has as input two values: $x_0$, $x_1$. The receiver has as input a choice bit: $b \in \{0, 1\}$. The sender receives no output, the receiver receives $x_b$, one of the two values according to its choice bit. A secure 1-2 OT instance should not reveal any information to the sender, in particular the sender should not learn anything about the choice bit of the receiver. Similarly, the receiver should learn nothing about the other value $x_{b-1}$. This is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1: OT Functionality

Oblivious Transfer

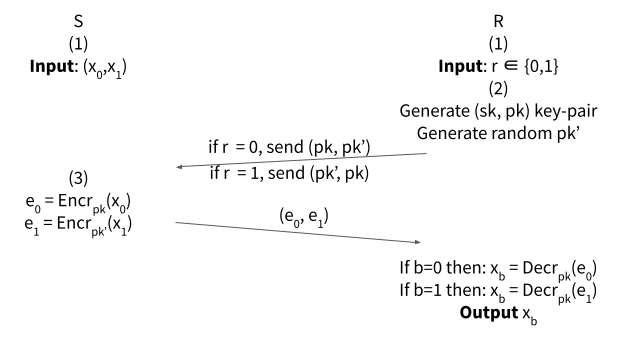

This is an example of a base oblivious transfer protocol for the semi-honest setting that uses public-key encryption [1]:

- $S$ has input $x_0$, $x_1$, $R$ has input $b \in \{0, 1\}$.

- Receiver:

- $R$ generates public-private key pair $(sk, pk)$, and a random public key $pk’$.

- If $b = 0$ then $R$ sends to $S$: $(pk, pk’)$.

- If $b = 1$ then $R$ sends to $S$: $(pk’, pk)$.

- Sender:

- $S$ encrypts $x_0$, $x_1$ with $pk$, $pk’$, such that: $e_0 = Encr_{pk}(x_0)$ and $e_1 = Encr_{pk’}(x_1)$.

- $S$ sends to $R$: $(e_0, e_1)$.

- Receiver:

- If $b = 0$ then $R$ decrypts $e_0$ with $pk$: $x_b = Decr_{pk}(e_0)$.

- If $b = 1$ then $R$ decrypts $e_1$ with $pk$: $x_b = Decr_{pk}(e_1)$.

- $R$ outputs: $x_b$.

Figure 2: Base OT

This protocol uses two public-key encryptions and one public-key decryption. It can be shown that oblivious transfer is inherently an assymetric primitive, and requires some form of public-key cryptography. However, as we will show next, we can greatly reduce the number of public-key operations for OT.

Oblivious Transfer Extension

It was first noted by Beaver [3] that it is possible to generate a polynomial amount of OTs from a small amount of public-key operations. The OT extension we present here is from Ishai et al (2003) [2], based on notation from [1, 4].

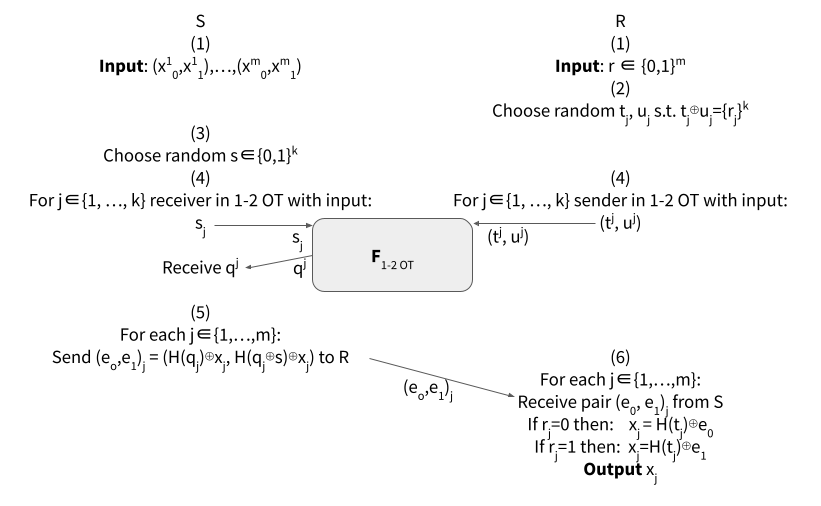

- $S$ has input m pairs: $(x^1_0, x^1_1), …, (x^m_0, x^m_1)$, $R$ has input m choices: $r \in \{0, 1\}^m$.

- Receiver:

- Let $T, U \in \{0, 1\}^{m \times k}$ bet two matrices, with $m$ rows $t_j, u_j \in \{0,1\}^k$ and $k$ columns $t^j, u^j \in \{0,1\}^m$.

- Choose $t_j$, and $u_j$ randomly such that: $t_j \oplus u_j = \{r_j\}^k$, for which $\{r_j\}^k$ is the $j$th choice-bit repeated k times.

- Sender:

- Choose random string $s \in \{0, 1\}^k$.

- Execution of $k$ 1-2 oblivious transfers:

- $R$ engages as the sender in the $j$th iteration of the OT with input: $(t^j, u^j)$.

- $S$ engages as the receiver in the $j$th iteration of the OT with input: $s_j$.

- $S$ receives from OT: $q^j$, which is either $t^j$ or $u^j$ depending on the choice bit $s_j$.

- Sender:

- For each $j \in \{1, …, m\}$, $S$ sends to $R$:

- $(e_o, e_1) = (H(q_j) \oplus x_j, H(q_j \oplus s) \oplus x_j)$

- Receiver:

- For each $j \in \{1, …, m\}$, $S$ receives from $R$ a pair $(e_o, e_1)$.

- If $r_j = 0$ then $x_j = H(t_j) \oplus e_0$.

- If $r_j = 1$ then $x_j = H(t_j) \oplus e_1$.

- Output $x_j$.

Figure 3: OT Extension

The key observation why this protocol works is that:

- If $r_j = 1$ then $q_j = t_j \oplus s$.

- If $r_j = 0$ then $q_j = t_j$.

Thus follows:

- If $r_j = 1$ then $e_1 = H(q_j \oplus s) \oplus x_j = H(t_j \oplus s \oplus s) \oplus x_j = H(t_j) \oplus x_j$

- If $r_j = 0$ then $e_o = H(q_j) \oplus x_j = H(t_j) \oplus x_j$

Knowing this the receiver can in step (6) decrypt one of the two $e$s:

- If $r_j = 1$ then:

- If $r_j = 0$ then similarly: $H(t_j) \oplus e_0 = x_j$

It is clear from the protocol that it only requires $k$ executions of a public-key based OT in step (4), generating a total of $m \gg k$ oblivious transfers:

- Number of public-key operations: $O(k)$.

- Communication: $O(m*k)$.

In comparison to the public-key OT protocol, the OT extension uses only a fraction $\frac{k}{m}$ as many public-key operations. This way we can achieve higher throughput. For example with security parameter 128, performing 128 base OTs takes around 0.3 seconds, whereas 1 million extension OTs takes around 1.4 second [5].

Discussion

We have shown that it is possible to execute $m$ instances of oblivious transfer using only $k$ instances of a public-key based oblivious transfer. What is an adequate choice of $k$ and $m$. As $k$ is the security parameter it has to be chosen suitably large. In practice this can be be around 80, 112, 128, etc. [5]. The choice of $m$ does not affect the security, and can be chosen arbitrarily high. However, there is a trade-off to consider for large versus very large $m$. Because the amount of transferred data is in the order of $O(m*k)$, the relative benefit of increasing $m$ diminishes whith increasing $m$, and furthermore, the latency of the protocol increases (if step (4) is blocking) with increasing $m$. Thus, it should be sufficient to set $m$ in the range 1 to 100 million for $k$ 128.

The presentation (link at the top) highlighted many other points which I haven’t mentioned here, check it out!

Follow-up Suggestions

Malicious oblivious transfer.

References

- [1] Evans, David, Vladimir Kolesnikov, and Mike Rosulek. Section 3.7 “A pragmatic introduction to secure multi-party computation.” Foundations and Trends® in Privacy and Security 2.2-3 (2017). URL

- [2] Ishai, Y., J. Kilian, K. Nissim, and E. Petrank. 2003. “Extending Oblivious Transfers Efficiently”. In:Advances in Cryptology – CRYPTO 2003. Ed.by D. Boneh. Vol. 2729.Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer,Heidelberg. 145–161.

- [3] Beaver, D. 1996. “Correlated Pseudorandomness and the Complexity of Private Computations”. In:28th Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing. ACM Press. 479–488.

- [4] Kolesnikov, V. and R. Kumaresan. 2013. “Improved OT Extension for Transfer-ring Short Secrets”. In: Advances in Cryptology – CRYPTO 2013, Part II.Ed. by R. Canetti and J. A. Garay. Vol. 8043. Lecture Notes in ComputerScience. Springer, Heidelberg. 54–70.

- [5] Asharov, G., Lindell, Y., Schneider, T. and Zohner, M., 2013, November. More efficient oblivious transfer and extensions for faster secure computation. In Proceedings of the 2013 ACM SIGSAC conference on Computer & communications security (pp. 535-548).